It is easy to see the derivatives market as a modern and recent addition to the economy. But how where and how did derivatives start to be traded? What is the history of derivatives?

Fast-paced percentage drops and gains on securities, real-time changes in commodity prices, rapid profits, and unexpected losses are largely isolated to computer monitors in the world of modern financial derivatives. However, the derivatives market has a long history that begins with the emergence of civilization itself.

Origins of derivatives

The first known example of this kind of transaction happened in ancient Greece, around 600 BCE, when Thales of Miletus, a philosopher, became the first olive oil derivative trader.

After many mediocre olive harvests, he used his knowledge in astronomy to predict a good season and negotiated with call options on olive oil presses for delivery in the spring. Things turned out as he had predicted and made a fortune out of it. This is also the very first example of a futures exchange.

The first options are traced back to olive trading in ancient Greece. The Athenians decided to use shipping contracts to stipulate prices, volume, and commodity types, this being the early origins of forward contracts.

Development of trade

The derivative market started because of the development of trade. The birth of what can recognizably be called a “derivative” coincides with the first codified legal code in history.

The Code of Hammurabi, the first cataloged legal text in human history, sets out strict regulations that protect farmers in the case of climatic disruption as stated:

“If anyone owe a debt for a loan, and a storm prostrates the grain, or the harvest fail, or the grain does not grow for lack of water; in that year he need not give his creditor any grain, he washes his debt-tablet in water and pays no rent for the year.”

The 48th law from the 282 laws can be seen as the first recognizable evidence of a derivative. Placed in a modern context the aforementioned law can be seen as the first put option, with the mortgage payments being voided in the event of a crop failure.

While this is the first mention of a derivative in operation, the usage of such processes reflects the agrarian nature of the 1800BCE Mesopotamian kingdom — derivatives until advert of complex imperial and industrial economics remained limited to agricultural markets.

Insurance, predictions, or hedging on the full specter of farming activities, whether that be that Mesopotamian farmer, the Greek olive grower of the 5th century BCE to Roman “expectancy” contracts from producers to consumers of the 2nd century CE demonstrate this.

The collapse of an empire

Trade and commerce, as much as farming, became essential components in the development of an ever more complex derivatives market.

With the expansion of more sophisticated global and regional economies following the collapse of the Roman empire and towards the Middle Ages, legally protected derivatives became important benchmarks for protecting commercial investment and cultivating trust in emerging markets.

Italian traders operating between city-states such as Pisa, Siena, Florence, and Venice from the 13th to 15th Century CE were at the forefront of the creation of such derivatives.

Derivatives beyond the Medieval Times

After the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire in the eastern Mediterranean maintained the usage of contracts for future delivery, which survived in the canon law of western Europe.

Sephardic Jews might have been responsible for “moving” the derivative trading from Mesopotamia to Spain during the Roman times, and then, to the Low Countries during the 16th century after being expelled from Spain.

Derivative trading spread from Amsterdam, England, and France during the 17th and 18th centuries, and then, to Germany during the early 19th century. During the 18th and 19th, banks and bankers were on the front line of derivative trading.

Contracts and agreements such as Commandas were a form of commercial partnership contract for maritime or land-based ventures for traders seeking commodities such as spices and silks in Asia.

Yet another form of derivative to emerge from this period was a Monti, which were shares issued by individual city-states to repay sovereign debt and were traded on secondary markets and acted as security in themselves.

Japanese rice futures

In 1697, in Osaka, Japan, The Dojima Rice Exchange emerged. It was a commodity futures exchange specializing in rice and is considered the world's first commodity futures exchange. In the late 17th century, rice played a very important role in the Japanese banking system, with banks and de facto banking institutions allowing their customers to deposit rice and withdraw cash.

At the same time, rice was and still is a staple of the Japanese diet, which generated a great demand for this commodity. In this environment, Japanese traders began to organize futures contracts in which buyers could purchase rice in advance at predetermined prices, eliminating the risk of sudden price increases and allowing them to secure valuable supplies of rice in advance.

These contracts enabled rice producers to obtain greater security for the sale of their crops by fixing prices at acceptable levels. Japan has been accredited for creating futures trading.

Derivatives until today

The classical and the Middle Ages witnessed initial innovation in the field of derivatives, importantly laying the foundations for more complex financial instruments as economics grew and became more diverse.

The next development in the derivatives markets came with the introduction of oceanic commerce and the growth of imperial powers between the 16th to 18th centuries CE.

Due to the expansion of empires such as Britain, France, Spain, and the Netherlands, merchants played a more invigorated and integral role in the maintenance of economies and gained hugely through their use of new derivatives.

Cities such as London, Amsterdam, and Antwerp overtook the traditional Mediterranean maritime-based economy, as commerce become oceanic in scope. It is in the Low Countries, modern-day Belgium, and the Netherlands, where the use of structured options becomes a key to managing merchant delivery dates and quality at delivery.

These options allow for the buyers to take up the delivery at the agreed conditions or to pay a fixed fee instead of taking the delivery. The development of such contracts created a sub-market, nominally exchanged on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, which was established in 1602, where profits and losses could be gained on speculative purchases.

As Dutch imperial power and trade rescinded in the 18th century, British commercial activity necessitated further expansions in the derivatives market. With the creation of financial institutions, such as the East India Company in 1600 and the Bank of England in 1694, derivatives became closely tied to the growth of the British economy.

The 17th century saw the emergence of an active market for securities. The most liquid ones, such as shares in VOC (the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or Dutch East Indian Company, founded in 1602), were the first ones to experience forward trade.

While derivatives, with their price being tied to a non-fixed expected price were prone to speculation, it is with the South Sea Company, based derivative that the first recognizable “bubble” can be seen.

In 1711, the South Sea Company, a joint-stock company, was established and provided with the exclusive right to trade with Spanish American colonies. Due to intense speculation by options and futures, the underlying stock value grew based on extravagant claims from the directors of the company. Influential figures such as Isaac Newton bought into what became a speculative craze that gripped 18th century Britain.

The bubble inevitably burst, however, when the grand statements and projections of the company resulted in nothing. The resulting panic in the financial market required Parliament to pass The Bubble Act of 1720 which limited the activity of all joint-stock companies without a royal charter and provided Parliament with the tools to regulate existing royal chartered companies.

The future of the derivatives market

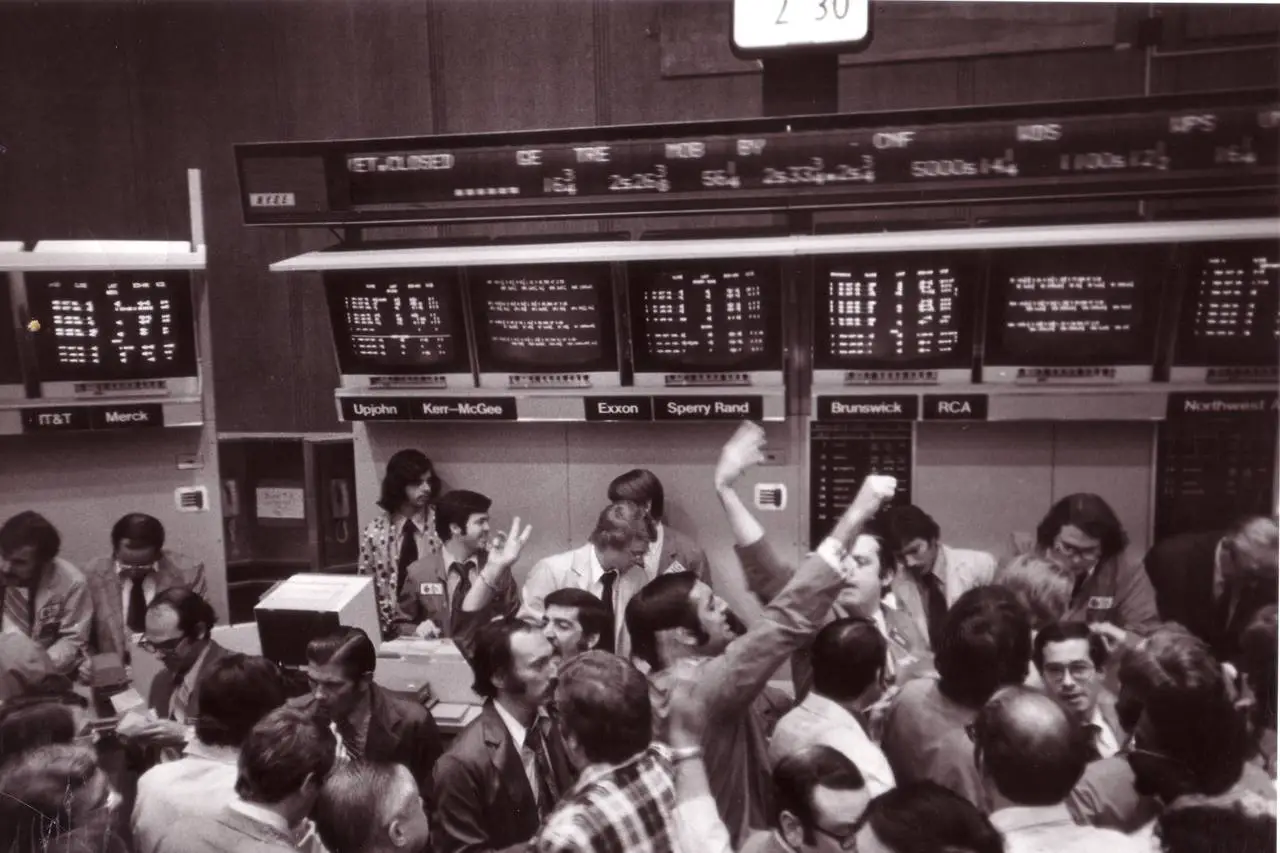

It is in the United States that a derivative market was developed that would ultimately guide the creation of the modern derivatives market. In 1848, the first derivative market was formed in Chicago under the name of the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT).

While being the oldest organized futures market still in operation, the underlying asset on which the derivatives are traded on the CBOT exchange is completely different than in ancient Mesopotamia.

Modern derivatives are evolved in their complexity with a range of assets now at the disposal of investors. The history of derivatives is one based on trade and farming with its history detailing this.

History of options trading

Russell Sage, a well-known American Financier born in New York, was the first to create a call and put options for trading in the US back in 1872. It was during 1977 that the number of stocks in which options could be traded started to increase.

The following years brought more options exchanges around the world, leading to the growth of the range of contracts that could be traded.

Mortgage derivative market

As the years went by, the Mortgage Derivative Market came. It was Lewis Rianeri who revolutionized household access to financing by developing a secondary market for mortgages, but abuse and speculation led to a disaster known as the subprime mortgage crisis.

Impact of derivatives in the financial crisis of 2008

Derivatives caused the financial crisis by creating artificial demand for underlying assets such as mortgages, credit card debt, and auto loans.

Between 2004 and 2006 the Federal Reserve began raising the federal funds rate. Many borrowers had interest-only loans, which are a type of adjustable-rate mortgage. Unlike a conventional loan, interest rates increase along with the federal funds rate.

When the Fed began raising rates, these mortgage holders found they could no longer afford the payments. This happened at the same time interest rates were reset, usually after three years.

As interest rates rose, demand for housing fell, and so did home prices. These mortgage holders found they could not make the payments or sell the house, so they defaulted, leading to one of the biggest stock market crashes ever.