One of the biggest speculative bubbles ever was Tulip Mania. But how did it start? How were the dutch fooled to believe a tulip bulb could be worth as much as a house?

In this article, we will analyze in detail what led to this speculative bubble, and what were the consequences.

Origins of tulips in Holland

The tulip is the flower that announces spring, it blooms only two weeks a year and its value is merely ornamental as it lacks odor and has no medicinal uses.

Originally from Central Asia, from there it was taken to Turkey, where tulips were highly valued in the Turkish Empire.

They entered Europe through the Austro-Hungarian Empire and from there they found their way to Holland, the richest country in Europe at that time.

Already in Holland, tulips began to be cultivated in botanical gardens. The tulip bulb is buried from late autumn to spring and dug up and visible the rest of the year.

If anyone wanted to buy a bulb and take it right then and there, they would have about five or six months a year. But, if there is impatience to acquire it, one could always sign a contract whereby someone agrees to deliver it once it's been dug up.

It doesn't sound very rational, as the idea that someone would want to sign a contract for a flower bulb is not what seems like a very convincing business idea, but this is what went on in Holland.

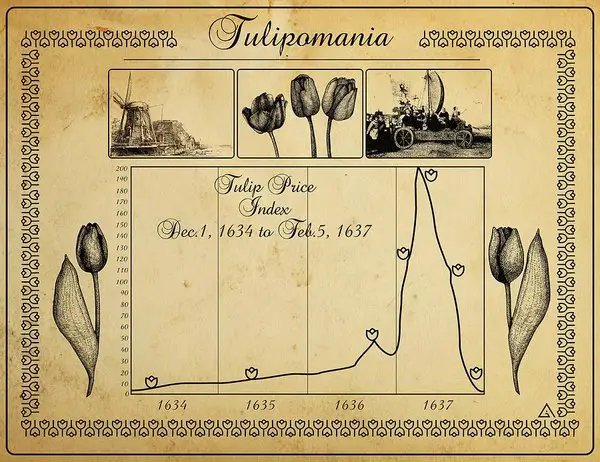

Tulip prices start to go up

The price of tulips began to skyrocket in 1620 due to the extravagant and growing demand of tulip lovers. As cultivation intensified, several beautiful-looking varieties, streaked with flaming colors, began to appear at random.

These were the most coveted and began to be called with very sonorous names at the same time that people began to pay higher and higher amounts for their bulbs. What the flower growers and buyers of the time did not know was that these iridescences were caused by a virus transmitted by the aphid.

In short, the bulbs that were sold at a higher price were diseased bulbs that would eventually die after a few plantings. In 1623 both tulip bulbs and tulip flowers reached exorbitant prices, so they began to attract speculators at the call of easy money.

How much was a tulip worth during tulip mania?

In 1623 a single tulip bulb could easily sell for 1000 guilders, and the highest price was about 5,500 guilders, the price of an affluent house.

The cultural values and social interactions morphed as the economy changed. A growing interest in natural history and a fascination with the exotic among the merchant class caused prices for these goods to rise sharply.

The influx of these goods also led men of all social classes to acquire specialized knowledge in the areas of new demand.

The exoticism of tulip bulbs caused a producing and buying euphoria, causing tulip prices to rise exponentially. Everyone wanted to invest in tulips, it was an ever-rising market, and no one could lose.

People even quit their jobs to grow tulips. This is common with other economic bubbles, where people quit their main jobs to engage in the activity surrounding the "bubbly" asset.

What is the main idea of tulip mania?

This mania was nothing more than a financial bubble where investors lost track of reality, thus producing the dramatic rise of a sector or asset which momentarily produces a cycle of positive feedback.

Hundreds of tulip catalogs were published at the time. Such was the euphoria, that many other crops were given up to grow tulips. Everyone wanted to participate in this lucrative business, from merchants to craftsmen and masons.

Then the tulip market entered the stock exchange. No one yet realized that the exorbitant prices made no sense and that a tulip crisis could occur.

Soon, the tulip business was no longer a seasonal product like all other crops and was traded all year round. The flowering of a tulip from cultivation takes 7 years, which was risky and did not fit in with the tulip buying euphoria in Holland.

How could a seasonal product be traded all year round?

The solution was to start selling tulip bulbs before they were harvested. Negotiating the price and purchase quantity before the bulbs were in bloom. As far-fetched as it might sound, this was one of the first steps to the emergence of one of the most important markets today, the financial futures market. (what caused the tulip mania?)

Tulip Mania Crash: What caused the tulip mania crash?

In early 1636, the traffic in tulips was so great that there was no choice but to accept them on the Amsterdam and other exchanges, and speculation skyrocketed. In an attempt to regulate the situation, special notaries were appointed to attest to the transactions: the "tulip notaries".

In towns or cities where there was no stock exchange, buying and selling were done through auctions in the main tavern, in an act presided over by the tulip notary who attested to the agreements made.

This exchange of transactions earned the name “Windhandel” (which means trading in the air). Because in the end, there was nothing more than papers exchanged between one and the other.

What had originally been a trade in tulips to decorate the houses, became pure and simple speculation where the least important thing was the bulb, and what was sought was to make quick and easy money.

At that time, a futures market was formalized, since the practice of agreeing to buy tulips by the end of the year had continued to grow. The legislation that was created for these operations required a cash payment of 2.5% of the total contract with a maximum of three guilders at the time of signing the agreement. It could not have been easier or more lucrative.

How tulip futures worked

Suppose subject A puts up for sale a bulb to be delivered in two months for 100 guilders. Subject B signs a futures contract that pays 2 guilders to subject A, and owes him 98. But B, who is a clever fellow, places his future with C for 150 guilders.

For this transaction B receives 3 guilders, thus recovering the 2 he paid to A, and also earns, in cash, one guilder, and when C pays him he will have made a profit of 50 guilders in two months.

But C, who is not a fool either, manages to sell it to D for 200 guilders. Again C receives 4 guilders and recovers with profit what he had paid to B.

At this point, the date arrives for digging up the bulb, which is already ready for delivery. At this time D owes 196 to C; C owes 147 to By B 98 to A. But, imagine that, at this point, the market price of that bulb has fallen to 20 guilders.

D refuses to pay C, probably because he does not have the 196 guilders he needs since no one has been willing to buy his right to the bulb. Then C refuses to pay B and B also refuses to pay A.

The situation is that there are three unfulfilled contracts to be settled. So it has to go to court, crowded with thousands of cases like this.

Tulip Mania bubble peak

This is what happened as of February 6, 1637. The day before, the bubble had reached its peak, but many were already beginning to suspect that things had gone too far and withdrew from the speculative game.

All the alarm bells rang when in the Dutch city of Haarlem, where a small lot of bulbs had been put up for sale, no buyer appeared. The news spread quickly, panic set in, and, in a few weeks, the bulbs depreciated by 95%.

As in all crises, the worst thing that can happen is that speculation has been leveraged by bank credits, because individuals may not get paid, but the Bank has to be paid. The State took charge.

Contracts signed before November of the previous year were declared null and void, and for recent contracts, buyers would be released from their obligation by paying 10% to the seller. The interesting thing is that the State changed the figure of "futures contracts" to another financial product called "call option".

Did tulip mania actually happen?

Many people wonder if the Tulip Mania was real. It did happen, but it didn’t have the catastrophic effects on Holland’s economy as many it’s been told.

In the end, no one went bankrupt over tulips, no one threw themselves in the canals, and only the people who could afford to lose significant money did so. The tulip bubble didn't send the Netherlands into an economic crisis.

Still, Anne Goldgar, an American historian, says the tulip bubble shook Dutch society differently. It brought about the idea that people could rise in society through speculation instead of hard work or a noble lineage.